A few days ago you brought your gelding in from the pasture where he’s been living 24/7. You decided to stable him during the day so you can get him prepped for an upcoming show. Today, however, he seems dull and is off his feed, with mild colic signs. The sudden change from pasture to hay and hard feed must have upset his digestive system. To avoid such scenarios it’s vital you’re aware of what constitutes good or poor horse feeding practices.

The above example demonstrates how our horse feeding practices can greatly affect our horses’ gastrointestinal (GI) health. In order to refine our management techniques, we need to first look at the diet horses evolved to eat.

Horse Feeding Practices following The Horse’s Natural Way

Horses evolved in an environment where they grazed more or less continuously—about 14 to 18 hours a day. And for good reason. Digestion in horses is less efficient than digestion in ruminants. Therefore, the horse’s feeding strategy is to eat a lot of forage to get the necessary nutrients required on a daily basis. Forage has a relatively rapid rate of passage through the digestive tract, producing lots of faeces. As long as the horse has plenty of forage, this rapid rate of passage doesn’t matter.

Horses evolved in an environment where they grazed more or less continuously—about 14 to 18 hours a day. And for good reason. Digestion in horses is less efficient than digestion in ruminants. Therefore, the horse’s feeding strategy is to eat a lot of forage to get the necessary nutrients required on a daily basis. Forage has a relatively rapid rate of passage through the digestive tract, producing lots of faeces. As long as the horse has plenty of forage, this rapid rate of passage doesn’t matter.

So this strategy works well for horses which wander, graze, and eat continually except when resting. However, a study showed that stabled horses maintained a lower (more acidic) pH in the stomach than those allowed to move around in paddocks. Movement also helps gut motility and this is why confinement is one of the risk factors for colic.

In natural settings, social contact also affects digestion. It gives horses a sense of security so they can settle down and eat. Being herd animals, the comfort of being together reduces their stress levels, promoting normal grazing behavior.

The three aspects (free movement, foraging, and social interactions) of normal equine behavior are disturbed when we confine horses in stables. By limiting free movement and feeding at set times, foraging behavior is lost. Even if they can see other horses when they stabled it’s not the same as having continual social contact. This also adds stress to their daily lives.

These changes can affect horses in several ways. Some of them adopt abnormal stereotype behaviour such as cribbing, weaving, and stable-walking. Additionally, health issues such as gastric ulcers, colic or laminitis can develop. And all these are down to the unnatural conditions, feeds and feeding practices of modern horse-keeping.

The horse’s small stomach is designed to handle continual modest amounts of high-fibre food. This is why horse feeding practices work best if the horse is trickle-feeding throughout the day and night. It can’t hold a large meal eaten all at once. Not only that, the horse’s gut also works differently from ours. Humans, like other predatory species, eat nutrient-dense meals (such as meat) and don’t have to eat again for quite a while. Horses are prey animals, eating a large proportion of fibrous material continuously to gain an equal amount of nutrients. They are constantly on the move, and on the lookout for predators.

By imposing our type of eating on the horse, thinking a horse can eat meals like us, we forget this is unnatural. It’s also detrimental to his well-being and gut health. We adopt a regime of feeding our horses just twice a day. We may even be restricting his forage, feeding in such a manner. Yet we don’t stop to think about the horse’s natural feeding behavior and how the digestive tract works.

Best Horse Feeding practices – Increase Chew Time

Foraging behavior— ie, grazing for 50 to 70% of the day—translates into heaps of time spent chewing. The horse spends a lot more time chewing forage than eating grain/hard feed. Studies have shown that for 1 kilogram of hay, a horse chews 3,400 times and takes 40 minutes to eat it. If a horse is chewing 1 kilogram of oats, he only chews 850 times and finishes it in 10 minutes.

Foraging behavior— ie, grazing for 50 to 70% of the day—translates into heaps of time spent chewing. The horse spends a lot more time chewing forage than eating grain/hard feed. Studies have shown that for 1 kilogram of hay, a horse chews 3,400 times and takes 40 minutes to eat it. If a horse is chewing 1 kilogram of oats, he only chews 850 times and finishes it in 10 minutes.

In another study, researchers looked at how many times horses chew per day when given constant access to hay: 43,000. By contrast, a horse consuming a pelleted diet chewed only a quarter of that amount, around 10,000 times per day.

Chewing is so important because the saliva it produces helps buffer the stomach from ulcer-causing acid. Therefore, we can increase chew time by making appropriate feeding adjustments. Feeding more fibre makes our horse chew more. The solid and liquid portions readily separate with he fibre floating on top forming a mat and the liquid underneath. There are also varying particle sizes.

By contrast, if a horse consumes a 100% pelleted diet, there’s not much physically effective fibre. This leaves the particle size very small in his GI tract . The horse doesn’t have to chew pellets as he would fibre, and there’s a very uniform mix of food within the tract. That uniform mixture will increase the risk for ulcers. It won’t move through the GI tract in the same way that a non-uniform mixture would. Primarily, because there’s not enough bulk to help keep things moving along properly.

Related Content: Journey Through the Equine GI Tract

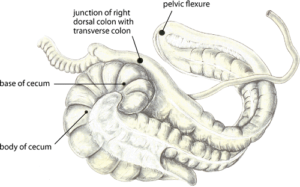

Studies were undertaken at Marion DuPont Scott Equine Medical Center, at the Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine. They studied feedstuff characteristics in the caecum of cannulated horses. (Those with surgical portals created through the abdominal wall through which researchers can access the caecum).

High-grain diets resulted in more material in the cecum that lacked good solid and fluid separation. The researchers noted that this mixture was also frothier and trapped more gas. A potential for colic.

Findings showed the caecum and colon come together at the pelvic flexure which is geared toward high-fibre forage that horses eat naturally. The more uniform mixture of modern diets might not fit as well, increasing the risk for gastrointestinal disturbances. In fact, more feed impactions occur at the pelvic flexure than anywhere else in the digestive tract.

Findings showed the caecum and colon come together at the pelvic flexure which is geared toward high-fibre forage that horses eat naturally. The more uniform mixture of modern diets might not fit as well, increasing the risk for gastrointestinal disturbances. In fact, more feed impactions occur at the pelvic flexure than anywhere else in the digestive tract.

So horses with minimal chew time are prone to not only gastric ulcers but also colic due to gas, impaction, or other issues.

Importantly, chewing also has a calming effect. Horses that chew more during the day are less likely to develop stereotypical behaviour. If they’re happily eating, they’re content, less stressed, and healthier.

Several things, however, can diminish a horse’s ability to chew. Poor tooth alignment, tooth loss, or arthritis in the jaw can all happen in older horses. He will chew less, with a higher risk for gastric problems. If the horse can’t chew fibre effectively, then you have to make dietary changes. Provide something that’s easier to chew, such as hay cubes, pellets, chaff, beet pulp, and/or a complete feed.

A Paper Trail of Feeding.

Keep precise records of what and when you feed your horse. This makes it easier to determine any causative factors if there are gastrointestinal problems.

This might include the type and amount of hard feed. Hay type and weight, feeding frequency, and diet changes.

Know the body condition of your horse and vital signs. Take these periodically so you’re familiar with his normal temperature, pulse and respiration rate when he’s healthy. It’ll help you to recognize problems early— for instance, if he goes off feed and his heart rate is increased. If any of these things are abnormal for that horse, it can be indicative of a gastrointestinal problem. You may think you know what’s going on, but a diary note is better evidence than a recollection.

Best Horse Feeding Practices – Reduce Meal Size

Remembering a horse’s small stomach size, concentrate meals should never be too large. Generally, a 500-kg horse should consume no more than 2.3 kg of concentrate feed per meal.

However, the new way of thinking for feeding horses correctly focuses more on the amount of starch in any one feed. To decrease the incidence of gastric ulcers yet still provide a high-starch meal to horses needing lots of energy, limit grams of starch per kilogram of body weight. Ie. no more than 2g of starch per kg of horse’s bodyweight. Ulcer prone horses should have no more than 1 gram of starch per kilogram of body weight in any single meal. For horses in less demanding work, some studies advocate no grain at all.

This means if your feed is 20% starch, your 500 kg horse should consume 2kg of feed per meal. If the feed is 40% starch, his meal should be half that size. This helps reduce gastric ulcer risk. Feeding more than this in one meal, increases the risk of hindgut acidosis or colic. Hindgut acidosis occurs when we overwhelm the small intestine with too much starch. It doesn’t get enzymatically digested and ends up in the hindgut. There are bacteria in the hindgut that love to digest starch and the end product of their starch digestion is lactic acid. This makes the hindgut more acidic which increases the risk for colic and indigestion.

Such horses might lose weight and develop stereotypies. Keeping a concentrate meal under 2 grams per kilogram of body weight may prevent hindgut acidosis.

Best Horse Feeding practices – Feed More Frequent Meals

Increasing the number of meals per day is a management strategy that helps reduce gastric ulcer and colic risks. However, it can be a challenging practice for people accustomed to only morning and evening feeding—before and after work.

Increasing the number of meals per day is a management strategy that helps reduce gastric ulcer and colic risks. However, it can be a challenging practice for people accustomed to only morning and evening feeding—before and after work.

Many horse owners put a pile of forage in front of the horse first thing in the morning or at night, thinking he’ll feed on it until the next feeding. The problem is most horses eat it all at once and by mid-morning or late evening the hay is gone.

Instead, try grouping smaller, more frequent fibre-rich meals closer together. Use a slow feeder for hay and incorporate some kind of chopped fibre (or chaff) into the grain or concentrate feeding. This will slow eating and make the horse chew more. If this is combined with some pasture access during the day, the horse will probably have less risk for gastrointestinal problems.

In fact, if you’re trying to get more calories into a horse, you’re better off feeding smaller meals more frequently. If you’re trying to feed just 1 gram of starch per kilogram of body weight, and the horse needs 5 kilograms per day (to keep weight on or provide energy for hard work), you should be feeding several meals. For example, feeding oats, which are about 40% starch, means you would feed four meals per day to keep it under 1.25 kilograms per meal. Not always a viable option of course!

Some of today’s commercial concentrate feeds can be helpful if they are high-fibre, or high in fat and fibre and relatively lower in starch and sugar. (around 20%)

Many stabled horses spend as little as 30% of their time eating. Dividing food into more meals so they can eat more often, is healthier for the GI tract than going so long between meals. Abnormal behaviors such as eating manure and bedding, or stereotypies eg chewing wood, are primarily due to the horse’s inability to graze. This means lack of chew time, insufficient fiber in the diet, and not feeling full. When a horse doens’t get his daily gut fill he’ll resort to trying to eat or chew other things.

Best Horse Feeding Practices – Make Diet Changes Slowly

As we mentioned earlier, when making any changes to your horse’s diet, do so slowly and gradually. Make any change over a couple of weeks. Eg. from hay to pasture or pellets and vice versa. From one kind of hay to another. Or in a concentrate ration, content, or quantity.

Related Content: Switching Horse Feeds Safely

Even moving from one part of the country to another, where feedstuffs might be different, can be a challenge for horses. Many people on the East Coast go from north to south every year for showing, racing, etc. When making these moves, bring a little feed (both the hay and concentrate) that the horse is accustomed to eating. Thereafter, make a gradual change after the horse arrives in his new environment.

Some horses adjust readily, others don’t, so always err on the side of caution when it comes to feeding practices. Horses are a lot like humans in that there are variations in how different horses handle change or different foods. This is down to a combination of genetic factors, microbes in the gut and differences in ability to handle different foods.

Take-Home Message

For optimum gut health, our horse feeding practices should mimic nature as much as possible. Unnatural conditions can adversely impact horses’ GI tract health and function. This means paying attention to what we feed (nutrient and fibre levels). Plus, how we feed in terms of meal size and frequency. We should always be mindful of trying to find ways to increase his eating and chew time.

If you’re unsure about your horse’s diet please feel free to contact us. Alternatively, try our free diet audit. Our Equine Nutrition consultant will thoroughly review your horse’s diet with the experience gained from over 30 years of practical, hands-on and common sense knowledge.

Reviewed and amended April 2021